With the Modi Government completing a decade at the helm, we take a retrospective view of its journey till date

Words by Karan Karayi

No tale can be fully told without understanding its main characters. And if one were to speak of the India growth story, it cannot be so without a retelling of the growth story of Gujarat.

This is perhaps best epitomised in the state’s annual ‘Vibrant Gujarat’ celebration, where a cornucopia comprising the Who’s Who of India Inc. lined up to pledge megabucks to the state, including Reliance, Tata Group, Adani Group, Suzuki, and ArcelorMittal, to name but a few. This industrial might is reflected in Gujarat’s standing in the economic universe, with the state ranked second in India, only behind Maharashtra.

In so many ways then, the state’s tale dovetails with that of the Indian growth story, where with Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the helm, India has exhibited both resilience and potential even in the face of global challenges. Global growth is expected to taper slightly downwards from 2.6% last year to 2.4% in 2024, while India is expected to steadily grow at 6.5% this year according to the IMF.

Even the most conservative of economists forecast India to grow at 6% or more for the rest of the decade, and investors and Big Business alike are swept away in a wave of optimism around the Indian growth story. But beyond pure growth projections, just how strong are the fundamentals of the Indian economy?

Evaluating The Economic Scorecard

Evaluating Mr. Modi’s economic performance necessitates a comprehensive review of the economic indicators and the impact of his significant reforms. The metrics reveal a mixed bag. While India’s growth rate supersedes that of most emerging economies, the labour market exhibits weakness, and private-sector investments have been disappointing.

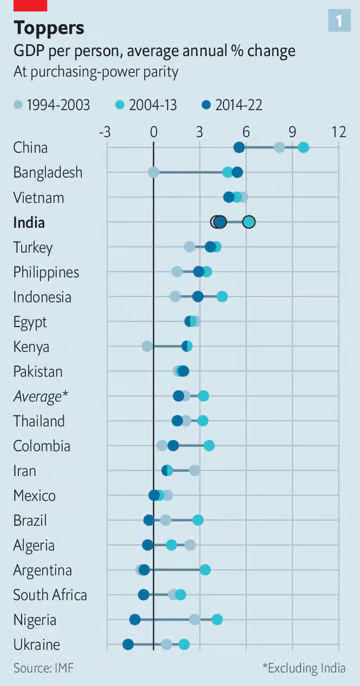

During Mr. Modi’s tenure, India’s GDP per capita, adjusted for purchasing power, grew at an average rate of 4.3% annually. This is a decline from the 6.2% growth rate achieved during his predecessor, Dr. Manmohan Singh’s tenure. However, it must be said that multiple contributing factors, including an infrastructure boom gone wrong, bad debt, slowing global growth, and the COVID-19 pandemic, have played a role in this slowdown, which is not a particularly Indian phenomenon and is instead observed across other large lower- and middle-income economies.

It would thus be more prudent to analyse PM Modi’s economic vision by evaluating progress across his three core objectives – formalising the economy, enhancing the ease of doing business, and bolstering manufacturing. His administration has made commendable progress in the first two objectives, while the results in manufacturing remain lackluster, although not for want of effort.

One significant change under Mr. Modi’s leadership is the transition towards a more formal economy, albeit at a significant cost. The stated goal was to shift away from the informal economy, dotted with smaller firms that avoid tax dragnets, to a formal one that is home to large, productive companies. And the way to achieve this was through the historic demonetisation policy.

The Controversial Demonetisation Policy

The demonetisation policy, executed in 2016, was one of Mr. Modi’s most hotly debated steps towards creating a formal economy. The move, which involved banning two large bank notes comprising 86% of currency in circulation, was implemented nearly overnight and aimed to invalidate the illegal earnings of the corrupt.

However, it inadvertently harmed the informal sector as household investment and credit plummeted, and growth likely suffered, even as those with large cash reserves found ways to funnel the funds into the banking system. The Rs. 2000 note, introduced to curb the menace of black money, was finally shown the door in 2023, with the RBI announcing its decision to withdraw the currency note from circulation starting 19th May 2023.

Digitisation and its Impact

Despite the fallout, demonetisation may have played a crucial role in expediting India’s digitisation. India’s digital public infrastructure now includes a universal identity scheme, a national payment system, and a personal-data management system. And while his detractors are quick to point out that these ideas were thought of under Manmohan Singh’s government, it has been largely built under Modi’s stewardship, and aligns with his demonstrated capacity to drive ambitious projects on a grand scale.

An example of this is the streamlining of welfare payments, which constitutes some 3% of GDP per year. Most of these transfers have been converted to digital payments, an initiative has proven more effective than the traditional physical distribution system, reducing the poverty rate from 19% in 2015 to 12% in 2021. Equally, it is common for most retail payments in urban areas to be made digitally, indicating a partial shift towards formalisation of the economy.

The Ripple Effect, and Introduction of GST Policy

As part of PM Modi’s efforts to bring larger sections of the economy into the formal fray, the Goods and Services Tax (GST) was introduced in 2017. Devised as a means of simplifying the complex web of state levies, it moves India closer to a national single market and enhances the ease of doing business on the back of a technology-first platform.

The revenue numbers are too strong to be ignored: GST collections rose to its second-highest level of all-time in January 2024, standing at Rs 1.72 lakh crore. This represents a 10.4% from the year-ago period, and represents a trend towards greater compliance and an uptick in economic growth.

But it is not all sunshine and roses. There is a greater need to bring tax rates under a singular umbrella, such as that of petroleum, but this is something that the broader political establishment has little appetite for. From that perspective, GST is the best middle road threading together diverse interests and governmental priorities across states. Walking this tightrope will remain a challenge for the foreseeable future, and the pragmatic approach taken by the centre has certainly paid off, even if the road ahead is long.

Boosting Manufacturing: Successes and Shortcomings

Make in India has been a major mantra of the Modi Government, with a $26bn subsidy scheme rolled out in 2020 to catalyse Indian manufacturing, and some $10bn pledged in 2021 for domestic semiconductor plants.

However, the value of manufactured exports as a share of GDP has stagnated at 5% over the past decade, and manufacturing’s share of the economy has fallen from about 18% under the previous government to 15% under the current one. Motley factors leave the manufacturing sector hamstrung, such as high logistics costs (for which physical infrastructure is being built at breakneck speed), rising inflation, inadequate scale of operations, a fundamental disconnect between know-how and investment, and poor productivity. Seen as a whole, these factors have stymied the growth of SME enterprises, a critical pillar of the manufacturing ecosystem.

Increasingly, there is an awareness of the need to drive employment for not just low or semi-skilled workers, but to find employment pathways for the talent pool in the agricultural sector if we are to move towards becoming a manufacturing-heavy economy. And while India can (and has) certainly benefited from nations and industries diversifying their supply chains in the wake of the pandemic, the window to seize the moment is growing increasingly smaller as supply chain plans start to firm up again after the dust settles.

At a high level, there has been a conscious effort to move towards high-value opportunities. This can be seen in the subsidy-to-capex ratio being in favour of IT hardware, medical devices, and telecommunications, banking on India’s competitive and high-quality talent pool to power it up the global manufacturing pecking order. This strategy, combined with positive externalities, could drive sustained growth in manufacturing and across the broader economy, but will need a further push to take India higher up the value chain.

Final Verdict

Truthfully, the impact of PM Modi’s policies will take years to fully materialise. While an investment boom could validate his approach, the strategy of using welfare payments as a substitute for job creation may prove unsustainable. However, many Indians remain cautiously optimistic about the economic transformations ushered in by their Prime Minister.

It must be said that the Indian economy, under PM Modi’s stewardship, has navigated through turbulent times and exhibited potential for robust growth. Despite the challenges, the administration’s commitment to reforms and initiatives has set the stage for what could be a promising economic future for India.