The road to the promised land might be paved with potholes, but India can navigate the road smoothly with some planning and a bit of luck

Words by Karan Karayi

As anyone travelling the length and breadth of India will attest to, traversing the nation often sees emotions oscillate between moments of optimism and uncertainty. All of these traits were on full display during India’s election season, and India’s economic blossoming has certainly been pointed out as momentous milestones on the national growth journey. PM Narendra Modi can certainly lay claim to presiding over the world’s fastest-growing major economy, which, with a GDP of $3.5 trillion, has now surpassed its former colonial ruler, the United Kingdom, to become the fifth-largest economy globally.

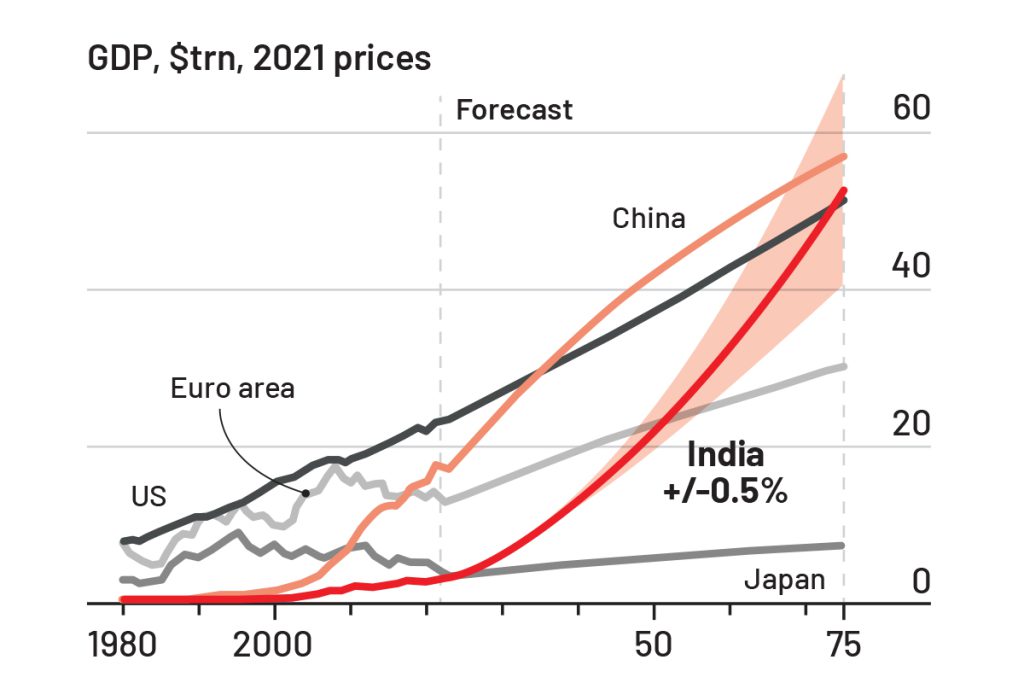

Experts the world over are fascinated by the Indian growth story, whose economy has averaged 6.4% growth over three decades. Bump that average up by half a percentage point, and it could even be the largest economy by 2070 if the cards fall in its favour.

However, much like Indian roads, India’s economic journey has not been entirely smooth, and instead pockmarked with potholes. Painful though it may be to admit, India has a history of premature celebration, marked by periods of great optimism belied by the lows of realising opportunities have been frittered away. For this writer, the finals of the ODI World Cup 2023 are a tiny example of this delight turned to defeat.

But for the purposes of this tale, it is essential to paint a picture as true to life as can be, and the truth is for all the economic inroads made and investments poured into civil and digital infrastructure, issues such as unemployment and labour force participation remain real issues of reckoning. Peruse this stat; India’s labor force is only 76% the size of China’s, while the percentage of women in the workforce akin to that of Saudi Arabia. Clearly, we have many promises to keep, and miles to go before we sleep.

Pursuing distinct growth models

As multinational companies pursue a “China plus one” strategy to diversify their supply chains, many are eyeing India as a promising alternative. The country’s growing clout is evident in various ways – from American firms employing 1.5 million people in India, more than in any other foreign country, to overseas companies looking to grow their employee base in India exponentially, to India’s stock market becoming the world’s fourth-most-valuable, and its aviation market ranking third globally.

However, India is not the “next China” when it comes to a manufacturing-led miracle. The country is developing at a time of stagnating global trade and the rise of factory automation, necessitating the need to pioneer a novel growth model. This model rests on three pillars: a massive infrastructure program to create a vast single market, the expansion of services exports (which have reached 10% of GDP), and a new welfare system that provides digital transfer-payments to hundreds of millions of poor Indians.

Economists of such eminent stature as Arvind Panagariya, a former Vice-Chairman of the NITI Aayog, has argued in his book ‘New India: Reclaiming the Lost Glory’ that India must walk on two legs – manufacturing and services – to achieve sustained growth in the decades ahead. This means streamlining labor laws, maintaining a competitive currency, and rationalizing tariffs to create a conducive environment for both sectors to thrive.

For his part, ex-RBI governor Raghuram Rajan said that India needs to firstly make the workforce more employable by improving education and skills of the workforce, and then creating jobs for the workforce it has. Clearly, India needs a distinct solution for its unique challenges.

Bridging the Divide: Formal and Informal Sectors

India’s path to growth has been unique, with its exports led not by manufacturing but by a productive yet job-poor IT and services sector. The country’s economic landscape is dominated by a handful of sprawling conglomerates alongside a long tail of small, informal businesses. Bridging this divide and creating mass employment opportunities will be crucial for sustaining India’s growth momentum.

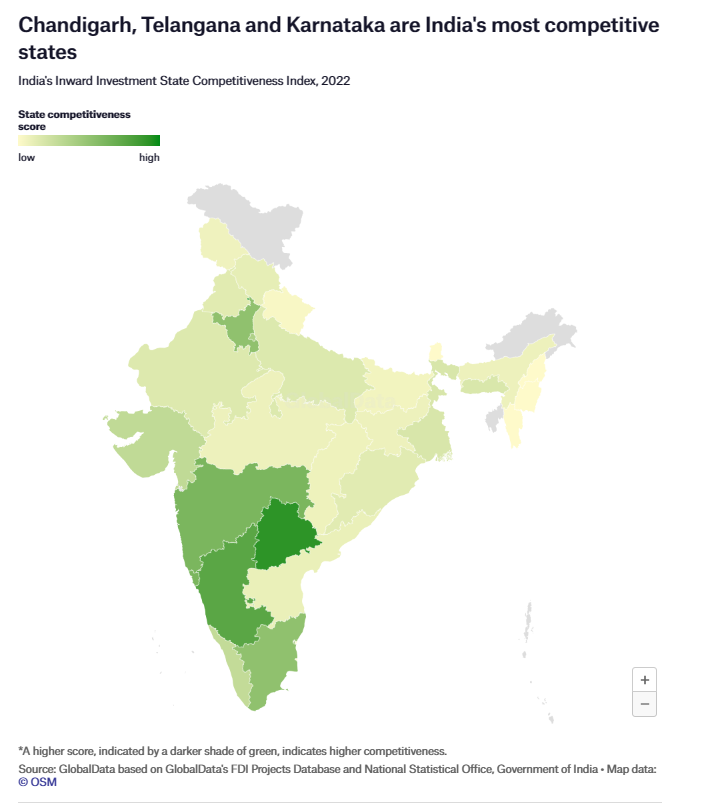

While the economic discourse often focuses on hubs like Bangalore and Mumbai, Prime Minister Modi’s ambition of Viksit Bharat that calls for transforming India into a ‘developed-country’ by 2047 requires a broader perspective. This vision involves equipping all 28 states to compete economically, offering business leaders opportunities beyond the prosperous south. Already, there are signs of this happening, with investments in remote states like Assam and Odisha, showcasing the country’s growing economic diversity.

Even so, there is much more that needs to be done. According to India’s Inward Investment State Competitiveness Index, Karnataka and Maharashtra are most competitive when it comes to attracting inward FDI, in no doubt spurred by their well-established financial and industrial ecosystems. But surprisingly, it is Chandigarh and Telangana that catch the eye for punching way above their weight.

Chandigarh’s score of 2.79 means that the diminutive Union Territory attracts 2.79 times its fair share of national greenfield FDI projects given the size of its economy. Despite accounting for just 0.17% of India’s gross domestic product (GDP), it manages to attract 0.48% of the country’s inward greenfield FDI.

Telangana isn’t doing too badly for itself either, at 2.58. India’s youngest state accounts for 5.01% of India’s GDP, but receives 12.89% of the country’s inward greenfield FDI, having attracted 160 greenfield FDI projects in 2022. It’s no small surprise that the majority of inward FDI in Telangana (91.8%) makes a beeline for its capital city Hyderabad, which ranked as the 11th-largest FDI recipient city globally in 2022 by number of greenfield projects, and fourth within Asia-Pacific.

Karnataka (2.11), Maharashtra (1.79), Goa (1.71), Haryana and Tamil Nadu (1.44) and Delhi (1.08) were the other states to demonstrate good competitiveness when it comes to attracting inward FDI, but much more is needed where this came from.

Navigating the Challenges of Reform

The idea of Modi as a strong economic manager is a key reason why Indians are likely to grant him a third term in office. However, India’s overall economic growth, which has averaged 5.6%, is not as strong as it has been in some years, but it compares very favourably with other world economies, and is in line with a broader global slowdown.

One area where Modi’s two terms have seen notable progress is the financial sector. The industry has been cleaned up and now enjoys growing global credibility, with the corporate sector boasting a return on equity above the global average. This reflects a healthier business environment, including the introduction of a national goods-and-services tax in 2017 that works across state lines.

India’s digital infrastructure has also become increasingly impressive, with the national identity system, Aadhaar, laying the foundation for a robust payment system used by 300 million Indians every month. This, in turn, has enabled most households to access bank accounts and receive welfare payments electronically, making credit more accessible.

Tackling the Labor Market Challenge

However, the economy’s shortcomings remain. The labour market is weak, with a majority of Indians underemployed or out of the workforce altogether. The unemployment rate for people aged 15 years and above in January-March 2024 was 6.7 per cent in urban areas, as per the 22nd Periodic Labour Force Survey, which represents a slight increase from the figure of 6.5% in October-December 2023, and a steady comparison with the figure of 6.8% for the March quarter of FY23.

In essence, this means a limitation on limits consumption, and exports do not make up the shortfall. Addressing these issues will require better cooperation between the central and state governments, as well as a more consensus-building approach from the Prime Minister, whose strongman style of management rubs opponents the wrong way at times.

Unlocking India’s Potential

Thirty years of gradual reform have laid a foundation for India to reach new heights. To achieve its potential, a new agenda as ambitious as that of 1991 is needed. This will involve tackling the country’s educational woes, improving urban governance to accommodate massive rural-to-urban migration, and fostering a thriving knowledge economy that rewards people for thinking for themselves.

As India gears up for another high-stakes election, the question is not whether Modi will win, but whether he, or whoever comes in, will evolve and rise above the norm. The path to realizing the country’s economic promise lies in tempering the politics of machismo that has defined India’s discourse in recent years, and fostering a growth mindset that can build on the good work done so far, and set the nation up for long-term success in the decades to come.