Artificial intelligence promises a new world of efficiency. But its massive energy demand is creating a new class of “energy deserts” and “pollution hotspots,” disproportionately harming the poor.

In a quiet suburb, or perhaps on the edge of an arid mesa, sits a vast, windowless building. It is the new factory of the 21st century. Inside, there are no assembly lines, no sparks, no steam. There is only the hum—a deafening, perfectly regulated chorus of fans cooling thousands of processors stacked in silent, black racks. This is the physical body of the digital cloud, the data center. And it is the engine of the artificial intelligence that is reshaping our world, from the C-suite strategy document to the daily weather forecast.

This engine is hungry. For a decade, leaders have pursued AI as a tool of frictionless, clean, digital transformation. They are now awakening to a very physical, very dirty reality. The computational power required to train a large language model or serve billions of AI-driven queries is herculean.

This is not a “cloud” operation; it is a terrestrial, industrial one. And like the factories of the industrial revolution, its environmental burden—its noise, its thirst, its pollution—is not shared equally.

We are building a new world of algorithmic efficiency, but we are building it on an old foundation of environmental inequity. The promise of “Equitable AI” is a dangerous illusion if the very infrastructure that powers it is fundamentally unjust. For leaders, this has created a new, systemic risk. The quest for a sustainable data center is no longer a public relations exercise; it is a strategic and moral imperative.

Rage Against the Machine

The sheer scale of AI’s appetite is difficult to comprehend. Before the generative AI boom, the world’s data centers already consumed between 1% and 1.5% of all global electricity, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). This was roughly equivalent to the entire energy footprint of Spain or the Netherlands.

Generative AI has thrown a match on that fuel, with the IEA estimating that the above figure has grown at 12% per year over the last five years.

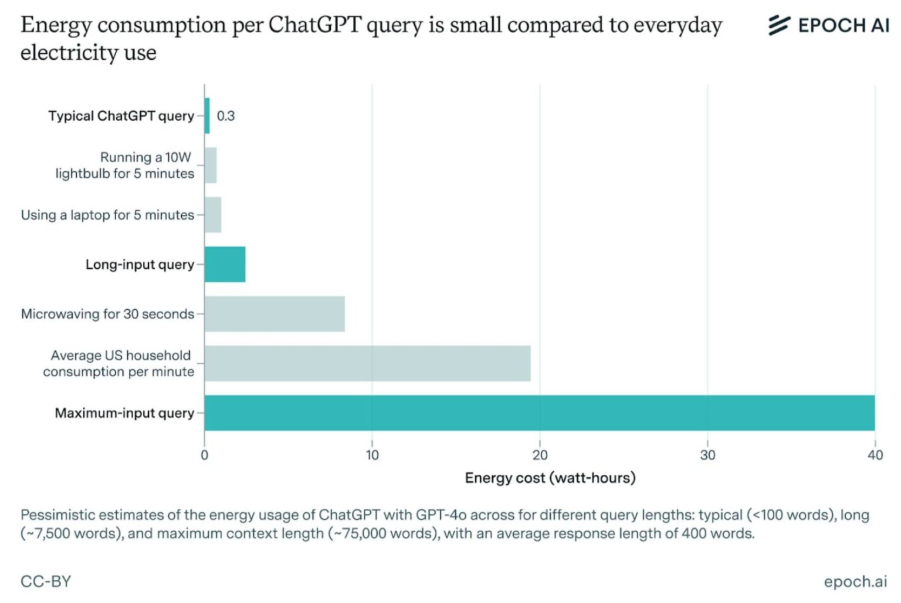

The training of a single model, like OpenAI’s GPT-3, is estimated to have consumed 1,287 megawatt-hours of electricity, producing a carbon footprint equivalent to driving to the moon and back 120 times. But the real cost is not in the one-off training; it is in the daily use, or “inference.” Research from 2023 suggests that a single generative AI query on a platform like ChatGPT consumes, on average, ten times the electricity of a simple Google search, with ChatGPT alone processing over 1 billion queries daily as of 2024. That’s approximately 260-500 MWh per day in terms of cumulative energy consumption for inference alone.

As companies embed this technology into every product, the demand curve becomes exponential. The IEA now projects that by 2026, the AI industry’s electricity consumption could be ten times its 2023 level. This is not a marginal increase. This is the birth of an entirely new, energy-intensive global industry, one that is already straining grids from Dublin to Northern Virginia.

This immense demand creates the first layer of inequity. When a single “hyperscale” data center campus requires a gigawatt of power—the output of a large nuclear power plant—it is not just using energy; it is competing for it. It competes with hospitals, schools, and residential homes. In tight energy markets, this surge in demand can contribute to rising utility costs for everyone, an invisible “AI tax” paid disproportionately by the poorest households.

The Geography of Sacrifice

This, however, is not the deepest problem. The more profound inequity is not just how much power is used, but where it is used and whose environment is burdened.

The data center industry is built on a specific logic: it seeks cheap land, cheap power, and a low-regulation environment. This combination is found most easily in communities with less political and economic power. In the 21st-century land rush for data infrastructure, marginalized and low-income communities are once again becoming “sacrifice zones.”

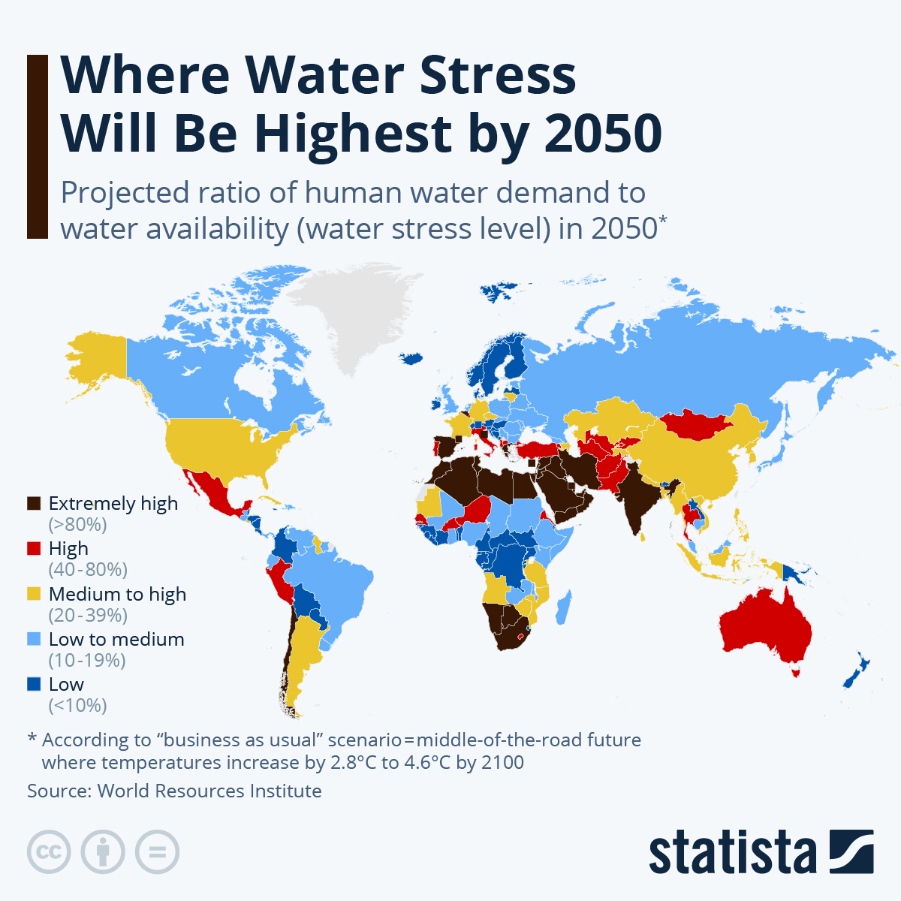

Consider the water. AI is thirsty. Those humming servers are cooled by vast amounts of water—evaporated in cooling towers at a staggering rate. A single large data center can consume between one and five million gallons of water per day, the equivalent of a small city. When that data center is built in a water-stressed, arid region—like Arizona in the American Southwest, or parts of drought-prone North Africa and India—it is in direct, existential competition with local farmers and residents for a life-sustaining resource.

Then there is the air. While tech giants like Google, Microsoft, and Amazon have all made admirable, high-profile commitments to match 100% of their consumption with renewable energy purchases, this is an accounting solution, not always a physical one. The grid, in most places, is not 100% renewable. When the sun is not shining or the wind is not blowing, a data center in Virginia or Ohio is often drawing power from coal and natural gas.

Worse, every data center is legally required to have a “failsafe”: massive, on-site diesel generators to ensure uptime during a grid failure. In many urban areas, these generator farms represent one of the largest and most concentrated sources of particulate pollution (PM2.5) and nitrogen oxides (NOx), key components of smog and respiratory disease.

These generators are disproportionately sited in poorer postcodes, the same communities already suffering from the highest rates of asthma and air-quality-related health issues. The digital utopia of one community is thus built on the toxic air and depleted water of another. This is the algorithm’s albatross: a systemic inequity that cannot be fixed with code.

A Path of Resilience, a Road to Equitability

What, then, is to be done? A resilient enterprise cannot be built on a fragile and unjust foundation. The C-suite must now see “data center strategy” as a core pillar of its “equity strategy.”

The first step is a technological pivot. The industry’s obsession with “Power Usage Effectiveness” (PUE)—a measure of energy efficiency—is a good start, but it is no longer enough. The new frontier is “Water Usage Effectiveness” (WUE) and “Carbon Usage Effectiveness” (CUE). This is driving a wave of innovation.

Microsoft is pioneering liquid immersion cooling, sinking servers into specially designed, non-conductive fluids. This is vastly more efficient than air cooling and uses a fraction of the water. In colder climates, like Meta’s campus in Luleå, Sweden, or Google’s in Hamina, Finland, “free air” cooling simply uses the cold northern air, while Google’s facility uses seawater from the Baltic Sea.

The most elegant solution, however, is turning the problem inside out. A data center is, at its core, a very large, very expensive heater. For decades, we have spent billions of dollars to waste that heat into the atmosphere. The new, circular model captures it. In Denmark and Finland, data centers are now channeling their waste heat directly into local district heating systems, warming thousands of homes and greenhouses. The data center evolves from an energy parasite to an energy partner.

The second step is a strategic and geographic pivot. A truly “equitable” data center strategy means abandoning the old logic of “cheapest land, least resistance.”

It requires companies to conduct rigorous “Community and Environmental Impact Assessments” before selecting a site. This means engaging with local residents not as obstacles to be managed, but as stakeholders to be partnered with. It means asking: What is the stress on the local grid? What is the state of the local watershed? Who benefits from the jobs, and who bears the environmental cost?

It also means a new partnership with the grid itself. Data centers, with their vast battery arrays, do not have to be a constant drain. They can be a stabilizing force. In Ireland, grid operators are experimenting with new rules that would pay data centers to feed power back to the grid or “power down” their non-essential tasks during peak demand. The data center becomes a shock absorber for the community, not the source of the shock.

Finally, this is a C-suite and governance imperative. The CFO must now ask for the WUE and CUE metrics, not just the PUE. The General Counsel must assess the regulatory and litigation risk of siting a facility in a water-stressed or environmentally vulnerable community. And the CHRO and Chief Diversity Officer must make the case that “equitable AI” is a fantasy if the company’s physical footprint creates environmental injustice.

AI promises to find patterns and solve problems beyond the scope of the human mind. What profound, tragic irony it would be if this tool, designed to help us overcome our limitations, was built on a physical foundation that automated our oldest, most destructive biases. The truly resilient enterprise of the 21st century will be the one that understands that its digital conscience is only as strong as its concrete one.