Even as EV sales surge, the huge gap that exists in charging infrastructure needs to be addressed

Raspreet Singh (name changed), a Mumbai-based entrepreneur, recently bought a new car at the turn of the year, like millions of others do. However, unlike most of them, Raspreet decided to get himself the very popular Nexon EV (Electric Vehicle), as he was sold on its combination of value, low running and maintenance costs, and practicality for Indian conditions. However, despite the fact that Raspreet regularly commutes from Mumbai to Pune, he is yet to take the car out on the Expressway, instead opting to make this journey in his older ICE vehicle. “Range concern is a very real issue, and I’m not sure of the infrastructure on the Expressway to charge the vehicle, or if it would even be available if I needed to charge mid-journey”, is how he explained his decision to forego the EV for road trips.

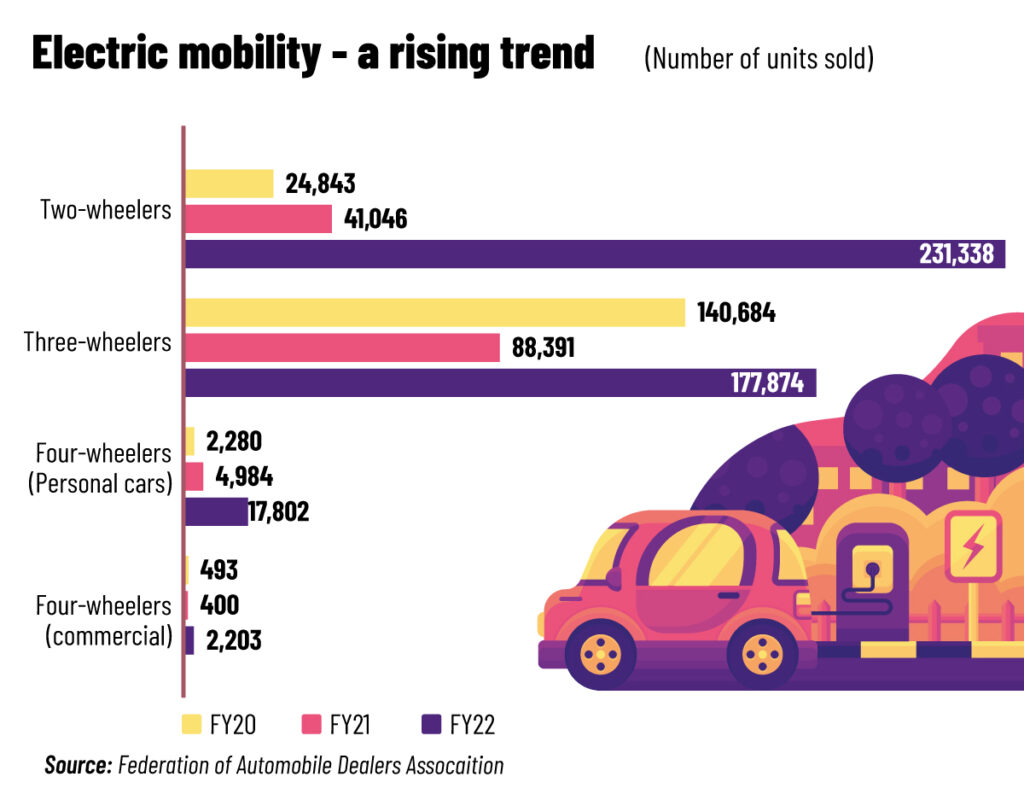

He is not alone in his thinking. Of the approximate 2,700 public charging stations with 5,500 connectors in India, most are concentrated in nine big cities and along highways and expressways. The government has set a target of setting up 10,000 public charging stations by 2025, but even that might not be enough. With approximately 45,000 to 50,000 EVs sold to end users this year, and that number expected to increase exponentially to about a quarter million by 2025, the need to develop India’s EV charging infrastructure in order to cater to this segment that is expected to represent 30% of all cars on the road by 2030, according to government estimates. And that’s before you even factor in the runaway popularity of electric two-wheelers in India.

The steepest hurdle to overcome is that charging. This isn’t as big a concern if you have enough space at your home, or don’t need to take multiple levels of permission to setup charging stations. But a major of people in urban areas dwell in high-rises, or large societies, and are often living in rented premises. Try convincing the managing committee or secretary to sign off an NOC, and you’d see why this is a daunting task. And this becomes even more difficult if you don’t live at a lower level of your building, or your parking (covered or otherwise) is some ways from your domestic meter.

The sheer number of variables at play and the nature of the opportunity at hand has created a unique ecosystem, where private players are throwing their hat into the ring to create the network of public stations, community charging stations (in societies), and high-speed chargers needed to power electric mobility solutions and get people like Raspreet from point A to B without worrying about driving range.

Smaller startups such as ChargeZone are helping deepen India’s EV charging network company, having recently completed the electrification of over 10,000 km of national highways by installing a network of 150 unmanned, app-driven, superfast EV charging points. In all, the company has set up 3,000 fast charging points across 815 EV charging stations, serving around 5,000 EVs on a daily basis, with plans to put up 1 million EV charging points by 2030.

Another leading operator, Statiq, recently sealed the deal with Rajasthan Electronics and Instruments, a joint venture between the Government of India and the Rajasthan government, to supply 253 fast chargers on four highway projects —Agra-Lucknow, Meerut-Gangotri, Chennai-Bellary and Mangaldai-Wakro. The company has several chargers in Jaipur, Beawar, Jaisalmer, Udaipur and Jodhpur. By year-end, Statiq aims to have a network of 20,000 charging stations, up from its current network of more than 7,000 chargers in over 60 cities to date.

And there are many more too, such as Sun Mobility, which seeks to address some EV ownership concerns of business and society – such as high up-front costs on account of the batteries, range anxiety, lengthy charging times, and scanty infrastructure – by offering a quick battery swapping model. They have so far deployed over 240 quick interchange stations across 18 cities, which has facilitated over 2.7 million battery swaps so far. Another player is ElectricPe, an EV charging aggregation platform, which has quickly built the most dense charging network in Bengaluru with 10,000 live charging points since its inception in May last year.

Bigger players too have fast-tracked their plans to enter the fray, such as Tata Power, with 3,600 public/semi-public charging points across 450 cities, with plans to set up over 5,000 charging points by FY23 and over 25,000 by 2028. Shell too plans to install more than 10,000 public charging points by 2030 in India, including 100 kW fast chargers to cut down on lengthy charging times for four-wheelers.

Government impetus needed

Simply put, green mobility is essential for India to achieve its net-zero targets over the next several decades. Uptake has been slow by consumers, with EVs share in total vehicle sales rising from 1.7% in 2021 to 4.7% in 2022 on the back of strong two and three-wheeler adoption. But more is needed to give this a fillip, such as boosting government spending, offering subsidies for infrastructure, and adopting favourable policies.

As bigger battery sizes become commonplace, the need for greater density and speed in the charging ecosystem becomes paramount, and government impetus could greatly help this. While EV subsidies rose around three times between 2021 and 2022—driven by a lower Goods & Services Tax (GST) rate on EVs and the FAME-II scheme that supports the electrification of public and shared transportation — policymakers need to earmark funds for the creation of charging infrastructure across the country, extend FAME-II beyond 2024, secure critical mineral supply chains in the medium-term, and support R&D investment into alternate battery technologies, such as solid-state batteries.

Late last year, Convergence Energy Services Limited (CESL), a government subsidiary, floated a tender for 3,000 land sites for the installation of charging and battery-swapping stations, but only 2,700 got awarded. The lack of subsidies could be behind this, as charging stations (especially high-speed chargers) are capital intensive, and the economies of scale don’t work for the government as asset utilisation is about 6-7%. It could well be a case of having to put the horse before the cart, and creating public charging infrastructure to match the demand for EVs, for it can be a positive flywheel for growing EV adoption, convincing many more Raspreet’s to hit their cart to the electric mobility bandwagon.